“Recreation and Transformation of Mandalas” Museum of Sacred Art, Septon, Belgium

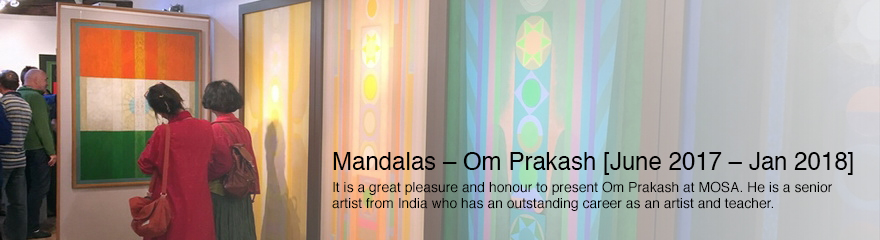

It is a great pleasure and honour to present Om Prakash at MOSA. He is a senior artist from India who has an outstanding career as an artist and teacher. I have had the opportunity to meet him on several occasions and go through his collection of works. I feel his art attracts those seeking spirituality as it conveys forms and colours in such a way that it puts us in touch with the inner world and just watching his works is a form of meditation that takes us away from the busy and stressful world of everyday life. I have seen how he keeps track of every work he has ever produced as if they are all children and need to be taken care of. He has kept track where every painting has gone and those in his Collection are very nicely kept by year or size or material. His art is very much appreciated both in India and the West. The show we are presenting at MOSA consists of 60 paintings spanning 5 decades as we have works from 1977 till 2016. There are many large works but also some small works on paper. There are amazing works that reflect the magical wonderful world of Mandalas. Om Prakash transforms and recreates this ancient Indian tradition in a way that is very personal to him. His works speak for themselves and I am convinced that they will speak to every observer and visitor to MOSA and uplift them to a higher consciousness and will awaken the desire to go within and start the process of meditation. We also hope that we will be able to bring this wonderful show to Museums or Cultural Centres around Europe. Now more than ever people need to encounter art that uplifts us and helps us look for inner peace.

– Martin Gurvich Director Museum of Sacred Art – MOSA

2016-17 - Marin County Foundation, Novato, California, USA

OM PRAKASH – An Introduction

By Patricia Watts

For the 57th solo exhibition of Om Prakash at Marin Foundation Galleries,

Novato, California – September 21st 2016 to January 12th 2017

Fall 2016 marks the fourteenth exhibition I have organized for the Marin Community Foundation since 2012. Most of the shows have focused on environmental themes and, more recently, on mature and under recognized artists of the North Bay Area. This exhibition, Om Prakash: Intuitive Nature, is not explicitly environmental, nor does it consist of work made by an artist from the Bay Area. However, the opportunity emerged because of my recent friendship with Justyn Zolli, a San Francisco painter, Zolli who is a protégé of Prakash and has spent time with the painter at his home studio in New Delhi, sought my advice last year on venues for a solo exhibition of the artist’s paintings. He then introduced me to Yogesh, Prakash’s son, who has lived in San Francisco for several years. I was struck by Prakash’s emphasis on the cosmic and by the maturity of his oeuvre, and together we decided to stage his first monographic exhibition in the United States.

In my travels to art fairs over the last two years, I would see Prakash’s paintings at Art Market San Francisco at Fort Mason and at Art on Paper at Pier 36 in New York at art dealer Evan Morganstein’s booth, Gallery Sam. Even before I met Zolli, I would introduce myself to Morganstein to let him know that I thought Prakash’s paintings were fresh and meditative while formally intriguing. The paintings reminded me of the work of a few North Bay painters of the 1950s and 1960s, who were influenced by Eastern philosophies. John Anderson, Richard Bowman, and Jesse Reichek come to mind with their abstract “inner worlds,” visualized by geometric forms, spirals, starbursts, and auras.

While doing research on Prakash for this catalogue, I was delighted to learn that he was one of eight artists selected by the late California painter Lee Mullican for the exhibition, Contemporary Indian Painting inspired by Tradition, presented at the UCLA Galleries in 1985–86. Mullican—who lived in the Bay Area from 1946 to 1952, before joining the UCLA art faculty in 1962—was part of the 1951 exhibition Dynaton, held at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and including the other mystical abstract painters Wolfgang Paalen and Gordon Onslow Ford. These artists were exemplars of the Bay Area interest in self-transcending awareness steeped in Eastern philosophy, and in Surrealism as well. The exhibition at UCLA presented a contemporary movement of Modern Indian Painters who built upon their own culture to develop mature styles focusing on nature, spirit, and the universe. Almost thirty-five years later, Om Prakash has proven himself to be deeply committed to the path of Indian Modernist abstraction incorporating a pure visual language to convey his personal or inner knowledge about the unity of all existence.

Earlier in his life, Prakash spent time in the United States—a critical period that has greatly influenced his work. He was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to attend graduate studies in fine art and art history at Columbia University and the Art Students League (1964–66). While living in New York City, he became acquainted with many well-known abstract artists, including Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Philip Guston, Jasper Johns, John Cage, Paul Jenkins, and Frank Stella. Upon his return to India, he continued teaching at New Delhi’s School of Planning and Architecture, from 1961-1981, and was the Principal of the College of Art from 1981- 1992. He has traveled throughout Europe and Asia, where he sought to experience the great works of art. His interest in Indian classical music and his decades of experience playing sitar have also greatly influenced his art. In addition to his painting practice, Prakash has also made collages, drawings, and life-size sculptures. The selection of eighty paintings and eight drawings for this exhibition was made from the artist’s website. The works were shipped from India by water freight across the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, then trucked from New York to Oakland over the summer. Om Prakash: Intuitive Nature is available to travel to additional US venues in 2017 and beyond, and the works will be incorporated into the family’s private collection, to remain in the United States indefinitely.

For the main catalogue essay, I sought a writer who could expound on Prakash’s paintings from an Eastern perspective within American culture, someone who could address abstraction through a multinational lens. I was aware of curator and writer Anuradha Vikram through her curatorial projects while she taught at UC Berkeley from 2009 to 2013 and worked at the Worth Ryder Art Gallery there, and aware also of her more recent position as Artistic Director at the 18th Street Arts Complex in Santa Monica. Vikram’s interests include transnational futurism and theories on globalization, as well as critical race discourse in modern and contemporary art history.

It has been a pleasure to work with Om Prakash and his family to bring his vital work to the attention of the San Francisco Bay Area. It is with great pleasure that we offer this exhibition and catalogue to continue an ongoing dialogue about the Eastern influences on American geometric and abstract art.

PATRICIA WATTS

Consulting Curator

PAINTING AS A CONDUCTOR: The Art of OM PRAKASH

By Anuradha Vikram

For the 57th solo exhibition of Om Prakash at Marin Foundation Galleries,

Novato, California – September 21st 2016 to January 12th 2017

Energy radiates through the paintings of Om Prakash. Color and line pulsate with vitality. Prakash channels the life-forces within and around himself into paintings whose precise geometries hover between abstraction and representation. With his cohort of artists, active in India since the 1960s, Prakash has synthesized ancient South Asian visual and spiritual traditions with the pictorial and formal values of mid-century Modernism in the United States and Europe, and other global traditions such as Chinese ink painting. While the artist is a student of painting traditions, he incorporates these forms alongside the teachings of nonobjective painting into a distinctly personal lexicon of shapes and symbols.

Prakash is known primarily as a practitioner of a uniquely Indian visual style, and his work as an artist and influence as an arts educator has been centered in New Delhi for much of his six-decade career. His interests are nevertheless international, and Prakash locates himself within a tradition including spiritually minded artists such as Mark Rothko, Ad Reinhardt, and Kasimir Malevich. Thanks to a postgraduate fellowship at Columbia University in the mid-1960s, he was able to meet some of these luminaries and compare notes at a formative point in his artistic development. To understand his approach in totality, one must apprehend the universally translatable elements and the culturally and personally specific aspects of the work simultaneously. The dialogue between twentieth-century Modernism painting in Prakash’s work plays out visually in two starkly different works, Mystery of Trees (2005) and Epiphany of Black (2007). In Mystery of Trees, Prakash abandons the stylings, with its deep color values and concentric, inscribed geometries, in favor of an allover composition in pastel greens, pinks, blues, and yellows. The resulting image is a geometric primavera, drawing parallels with the line and color work of Paul Klee. Flat and patterned like a scrim, the painted surface opens just enough to suggest an early morning light filtering through the tall trunks of a forest. In Epiphany of Black, Prakash evokes the black-on-black crosses of Ad Reinhardt and the resonant squares of Josef Albers. Deep red pulsates from the painting’s center, framed by rich blues and soft purples. Squares and rectangles radiate outward with a muted rhythm. The deep black surface recedes and colorful geometries advance, conveying a breathable stillness. Both works are marked by the luminosity that is Prakash’s signature, whether in the prismatic sunset vista of Orange Light (2009), or glimpsed obliquely in the off-kilter Counterpoint Mandala (2012).

Born in 1932, Prakash was fifteen years old at the time of India’s independence, and he came of age among a generation of young Indians who sought to define the newly postcolonial nation through culture—specifically, renewed interest in South Asian classical arts. For Prakash, who plays the sitar, this came to include the Hindu Raga, a tone poem with religious reverberations that also marks the weather or the time of day.

Musical influences infuse the visual rhythms of his paintings. Music is a consistent source of inspiration for twentieth century Modernist painters, whether it be Kandinsky incorporating Stravinsky, or Stuart Davis channeling American jazz. Music operates similarly in Prakash’s paintings, inspiring an undulating rhythm of color and line.

At the same time, the raga proposes possibilities for painting that Western Modernism generally has not. This is music composed with intention to not only reflect the specific season and time at which it is performed but also to inform and influence that moment of performance on a metaphysical level. A Malhar, or rain Raga, does not simply celebrate the monsoons: the song has the potential to bring the rain. In the painting tradition, images are also invested with affective power. A lexicon of geometric forms represents specific spiritual aspects, deities, and principles which can be brought to bear on the viewer’s mental and physical state, thanks to the artist’s act of focusing those energies.

Rain tones prevail in Prakash’s Tilak Malhar (2015). Circles inscribed within squares in the traditional mandala pattern double as raindrops and as moons in different phases. The blues of the painting’s surface are marbled with textures of wetness. This painting communicates the sensation of a cool summer rain in the garden, contrasted against deep floral tones and luminous greens. Still, there is more to the invocation than mere resemblance. Circles within circles offer a cyclical or calendrical reading in which the passage of time and the phases of life and death are revealed. Circular Spectrum (2013) reflects the first drops of rain splashing into a mandala of concentric ripples that expand infinitely into space. As did the Cubists, Prakash represents many moments in time and space simultaneously.

In the Western tradition, this power to affect other bodies across a distance through art is known as phenomenology. German Romantic theorist Edmund Husserl introduced this secular concept, derived from Hindu and Buddhist transcendental philosophies, into European discourse in the late nineteenth century.Modernist painters including Mark Rothko, Ad Reinhardt, Agnes Martin, Ellsworth Kelly, and Barnett Newman hinted at phenomenology with their use of color fields and of contrasts that trigger physical Om Prakash. Mystery of Trees -2005, 55 x 40 inches. Effects in the viewer’s eye or recede into dialogue with the walls behind. American artists since the 1960s—most notably the group identified with Land Art and the Light and Space movement—have explored “the expanded field” of phenomenology in sculpture and site-specific installation. Still, it is only recently that these ideas have gained traction in painting discourse. Spiritual and metaphysical questions in painting are likewise not new, but they are newly taken seriously—though not always consistently so. Perhaps the global conversation has finally caught up with Prakash.

Massimiliano Gioni’s 2015 Venice Biennale linked a tradition of devotional painting, anchored in the northern state of Rajasthan, with early twentieth-century European Spiritualist artists such as Hilma af Klint. While this connection is viable, it is incomplete without the inclusion of Om Prakash. The twentieth-century South Asian artists also pioneered a contemporary tradition of Modernist, metaphysical, phenomenological paintings which originated from an urban perspective on South Asia. Furthermore, they operate within systems of artistic training, agency, authorship, and economics on the same footing as Western artists – a claim that cannot be made of the Rajasthani painters whose work circulates as anonymous “folk art.”

Though Prakash is a Modernist painter, motivated by a personal artistic vision, and not a religious artist, his work is underpinned by considerable knowledge of philosophy. Certain principles prevail: the order of the universe is in all things, and in all things the underlying structures are the same. Change is a circle, stability a square. Male is an upward thrust, female plunges down. Harmony, balance, and illumination are virtues. Action and inaction are equal and opposite forces. Ego is absent. Mandala – Union of Opposites (2012) articulates these principles through a colorful grid of squares and triangles, incorporating tones from light to dark and colors across the spectrum into a diverse and harmonious composition. Here again, ephemeral light emanates from the work’s core. The Mandala of Squares might read visually as a field of pixels, a quilt, a chess board, or one of Sol LeWitt’s iterative grids. Indeed, iteration—repetition that begets change – is central to the vision of the universe.

Among the great proponents of iteration was Josef Albers, whose signature series Homage to the Square is likely to be more recognizable to an American audience. Parallels between Albers and Prakash are not limited to their shared dedication to teaching. The two artists represent different understandings of related ideas, translated through two distinct cultural traditions. The use of the square in Prakash’s tongue-in-cheek Selfie 2 (2014) makes that clear. Prakash’s “selfie” is a nonobjective grid of concentric squares, graded from white to deep yellow, then pale purple. This work demonstrates Albers’s theory of color interactions, though Prakash has arrived at his perceptual effects through his study of the South Asian tradition. Prakash’s squares are embedded in a larger, dark red square, highlighted by a square cruciform, in bright reds, greens and pinks. The surrounding pattern makes subtle reference to a distinctly South Asian tradition of drawing and painting as anchored to architectural space.

A teacher of art for many decades, as well as a faculty member/Principal and administrator at the College of Art, New Delhi, Om Prakash has outlined the four categories of artistic expression as they correspond to yogic principles. These are: physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual. Importantly, Prakash stipulates that only the first three categories can be achieved through the artist’s intention, plan, and action. The spiritual may reveal itself, or it may not. One can therefore think of Prakash’s extensive body of work, spanning over six decades of prodigious output, as a daily practice of seeking. With each painting, the artist creates a circuit to conduct metaphysical action. Having created the conditions for new visions, he now invites us to stop, contemplate, and open our minds to unseen possibilities of art and experience. The viewer may experience a charge.

ANURADHA VIKRAM

Anuradha Vikram is a writer, curator, and educator, and Artistic Director at 18th Street Arts Center in Santa Monica, California. She writes frequently for the art publications X-TRA, Daily Serving, Hyperallergic, and Artillery. Vikram holds an MA in Curatorial Practice from California College of the Arts and a BS in Studio Art from New York University. She is a Senior Lecturer in the Graduate Public Practice program at Otis College of Art and Design, and has curated over 40 exhibitions and residencies in non-profit, academic, and commercial venues.